You know about New Year’s Eve—the countdowns, the fireworks, the half-hearted resolutions—but have you heard of New Year’s Season? Because in India, it’s not about one night of celebration. It’s an entire season of fresh starts, sacred rituals, and a festival lineup that stretches across states, cultures, and calendars.

Here, the New Year doesn’t just reset your diary. It resets your energy. Your intentions. Your spirit. From the calm of the Ganga to the bustle around the Brahmaputra, every region has its own reason, rhythm, and ritual to welcome the new year—and honestly, that’s what makes it so fascinating. It’s not just a celebration. It’s a soulful reboot.

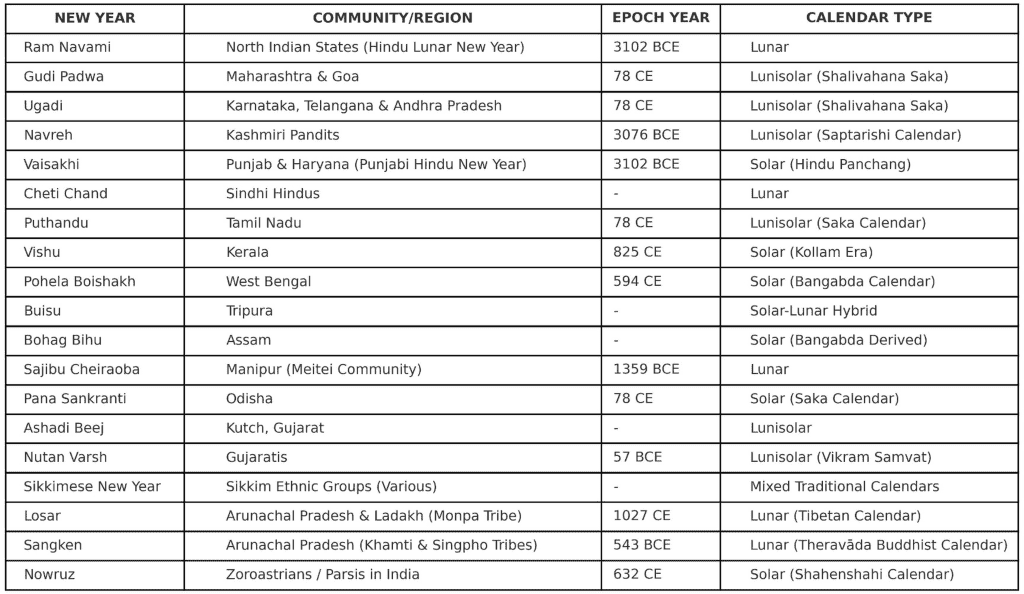

Unlike the universally accepted January 1st, Indian New Year isn’t tied to a single day or even a single calendar. It flows according to ancient timekeeping systems—lunar, solar, and lunisolar—each adding a unique touch to when and how people decide to say “Happy New Year.” So let’s take a deeper look at the faces of the Indian New Year, state by state, tradition by tradition.

Why Does India Have Multiple New Years?

In India, New Year is basically that friend who refuses to arrive fashionably late or on time—instead, they just show up whenever it feels right, and somehow, it works whether you have an understanding of Vikram Samvat calendar or Saka calendar, Indian New Years are observed as a local festival in the hearts of every villages and people following traditions even in today’s modern cities.

That’s because time in India isn’t just about tracking days—it’s deeply tied to culture, geography, faith, and ancient astronomy. So naturally, we don’t have just one New Year. We’ve got a whole bunch.

The Role of Lunar, Solar, and Lunisolar Calendars

Let’s break it down:

- The lunar calendar follows moon cycles.

- The solar calendar keeps up with the sun’s movements.

- And then there’s the lunisolar calendar—basically the overachiever that balances both.

Hindu timekeeping, especially, leans heavily on lunisolar systems. These months run by the moon, but they throw in an intercalary (leap) month now and then to catch up with the solar year. It’s detailed, meticulous, and honestly kind of brilliant.

This diversity in calendars isn’t a glitch. It’s a reflection of how India functioned as a patchwork of kingdoms and dynasties, each developing their own system of marking time. That patchwork still shines through in our festivals today.

Zoom out, and you’ll see this isn’t just about timekeeping. It’s about identity. The way India celebrates New Year is hyper-local—language, food, customs, even the meaning of “a new beginning” shifts from one region to another. That’s why in India, New Year isn’t a timestamp—it’s a cultural expression.

While most of the world syncs their watches to January 1st, India waits for the right harvest, the right stars, and the right season. Here, time is emotional. It’s spiritual. And it’s deeply, unapologetically rooted in the land.

Influence of Harvest Cycles and Astrology on Indian Regional New Years

At its core, India is an agrarian society. Always has been. The land tells us when to sow, when to reap, and when to pause and celebrate. That’s why a lot of Indian New Year festivals are perfectly timed with seasonal transitions and celestial alignments.

So when a region celebrates New Year, chances are they’re also celebrating a good harvest, an equinox, or a cosmic event that feels just right to begin again.

- Take Baisakhi in Punjab and Bohag Bihu in Assam—both lined up with the Rabi harvest. A time of abundance and community thanksgiving.

- In Kerala, Vishu aligns with the vernal equinox and opens the year with Vishu Kani, a carefully curated display of auspicious items meant to bless the year ahead.

- A lot of regional New Years also start on the Chaitra Shukla Pratipada—the first day of the bright half of the Chaitra month. That’s no coincidence—it’s an astrologically loaded day.

- Another big one is Mesha Sankranti, when the sun enters the Aries zodiac sign. It’s considered one of the most spiritually charged transitions of the year and anchors festivals like Puthandu, Vishu, and Pohela Boishakh.

- Even food takes on astrological symbolism. Like Ugadi Pachadi, a dish made with six different flavors during Ugadi Festival in Andhra Pradesh—sweet, sour, bitter, salty, pungent, and astringent. These aren’t just tastes. They represent life’s full emotional range—from joy to sadness, surprise to disgust. A whole mood board in a bowl.

Major Indian Regional New Year Festivals

Let’s get into the good stuff—the actual festivals. Each of these is more than a date. It’s a portal into how communities celebrate, reflect, and reconnect.

Ram Navami – North Indian States

Usually falling in March or April, Ram Navami celebrates the birth of Lord Rama. It also serves as the Indian New Year marker in states like Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Himachal Pradesh, and Madhya Pradesh.

Celebrated on the ninth day of the Chaitra month, it’s known across the country as part of Chaitra Navratri—the Hindu Indian Lunar New Year. It’s tied to a pretty epic timeline too, as it’s believed to signal the beginning of Kali Yuga in 3102 BCE.

Devotees fast, visit temples, and recite Ramayan verses—welcoming the year with calm, clarity, and faith.

Gudi Padwa – Maharashtra & Goa

This is how the west coast throws a New Year party. Gudi Padwa, observed on the first day of Chaitra month in the Shalivahana Saka Calendar (which started in 78 CE), kicks off with rangoli, sweets, and a towering Gudi hoisted outside homes.

The Gudi itself is iconic and marks as a symbol of Hindu Nav Varsh—a bright new saree pleated and draped over a bamboo stick, decorated with neem or mango leaves, flowers, sweets, and topped with a brass pot.

Legend has it, this tradition started with King Shalivahana after his victory over the Shakas. Whether myth or history, today it stands as a symbol of resilience, prosperity, and pride. Maharashtrians and Goans celebrate it with unmatched energy—and honestly, it’s hard not to get swept up in it.

Ugadi – Karnataka, Telangana & Andhra Pradesh

Same day as Gudi Padwa, but this time in the southern belt, the vibe shifts into Ugadi mode—known as Yugadi in Karnataka and Ugadi festival in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana.

The star of the show? Ugadi Pachadi, a dish with five flavors that mirror life’s emotional rollercoaster. You’re not just eating—you’re spiritually preparing for every up and down the year will bring.

This festival is also about cleansing—both literally (with oil baths and house cleaning) and figuratively (with prayers and introspection).

Navreh – Kashmir

Observed by Kashmiri Pandits, Navreh feels intimate and deeply rooted in time. Based on the Saptarishi Era Calendar that traces back to 3076 BCE, this New Year begins with the quiet ritual of preparing the Navreh Thali.

It’s a platter full of symbolism—rice, curd, walnuts, wheat cakes, coins, herbs, and fresh flowers—all meant to summon abundance, balance, and clarity in the year ahead. It’s less about spectacle and more about spiritual reset.

Vaisakhi – Punjab & Haryana

Vaisakhi isn’t just a New Year—it’s a full-blown cultural high. In Punjab and Haryana, this festival checks all the boxes: historical, spiritual, and agricultural. On one hand, it marks the Punjabi Hindu New Year, tied to the Hindu Panchang calendar that begins way back in 3102 BCE. On the other, it’s a massive day for Sikhs—it commemorates the formation of the Khalsa Panth by Guru Gobind Singh Ji in 1699 CE.

But let’s not forget the farmers. Vaisakhi is also about reaping the Rabi harvest, which means prosperity, gratitude, and celebrating the Earth’s abundance. Whether you’re dancing bhangra, visiting a gurdwara, or joining in a village fair, Vaisakhi is all about renewal with a dose of pride.

Cheti Chand – Sindhi Hindus

For the Sindhi community, New Year arrives in style with Cheti Chand. It celebrates the birth of Jhulelal, their patron saint, and is as much a spiritual observance as it is a cultural reunion. The day is steeped in symbolism: water processions, colorful rallies, devotional songs, and a whole lot of community bonding.

Falling on the first day of the Sindhi Tipano calendar, Cheti Chand is celebrated across regions where Sindhis have made their home—be it Gujarat, Rajasthan, or anywhere across India and beyond. It’s heritage, faith, and celebration rolled into one.

Puthandu – Tamil Nadu

Puthandu, the Tamil New Year, follows the Saka calendar, just like Gudi Padwa and Ugadi. But down south, the celebration hits different. Early morning, Tamil households set up a vibrant visual called the Kanni—a plate loaded with mirror, flowers, fruits, gold, and sacred books. The idea? What you see first shapes your year.

There’s also a ton of feasting (hello, Mango Pachadi), prayers, and family time. Puthandu isn’t loud or showy—it’s calm, symbolic, and spiritually grounding, like a breath of fresh, jasmine-scented air.

Vishu – Kerala

If there’s one festival that blends tradition with cinematic beauty, it’s Vishu in Kerala. Falling in line with the Kollam Era that began in 825 CE, Vishu celebrates the agricultural New Year and the zodiac entry of the sun into Mesha Rashi (Aries).

At dawn, you wake to see the Vishukkani—a basket of prosperity arranged with mirrors, gold, grains, fruits, and lamps, placed in front of Lord Vishnu or Krishna. That image is your first blessing for the year. Add in firecrackers, gifts from elders, and a delicious Vishu Sadhya (feast), and you’ve got yourself a day that hits all the right notes.

Pohela Boishakh – West Bengal

Pohela Boishakh isn’t just Bengal’s New Year—it’s a cultural moment. Rooted in the Bangabda calendar, created during Emperor Akbar’s reign in 594 CE, this festival was designed to help with agricultural tax collection. But over the centuries, it morphed into something much bigger.

Now, it’s a day of parades, music, and food. You’ll see people in crisp white and red, bookstores buzzing with readers, and families crowding sweet shops. And the food? Think ilish maach (hilsa fish) and sweets that melt your soul.

Buisu – Tripura

The Tripuri New Year, called Buisu, happens right after harvest season. It’s low-key, joyful, and all about embracing prosperity. There are traditional dances, indigenous foods, and rituals passed down through generations.

You won’t see giant parades, but what you will find is a celebration that’s honest, heartfelt, and deeply tied to the land. It’s a reminder that beginnings don’t always need bells and whistles—sometimes, they just need community and cultural pride.

Bohag Bihu – Assam

In Assam, New Year arrives with the most beautiful kind of chaos—Bohag Bihu. It’s a week-long celebration that blends agriculture, music, love, and laughter. Known also as Rongali Bihu, this festival is all about fertility, harvest, and fresh starts.

There’s dancing in open fields, people gifting each other handwoven gamochas, and evenings echoing with the beat of the dhol. If a festival could be a song, Bohag Bihu would be a folk anthem with a happy chorus.

Sajibu Cheiraoba – Manipur

In Manipur, the Meitei New Year is called Sajibu Cheiraoba, and it brings with it a quiet kind of symbolism. Rooted in the lunar calendar and tracing back to King Maliya Fambalcha (1359–1329 BCE), this festival is about cleansing the home, cooking sacred dishes, and offering prayers.

And then there’s the hill-climbing. Families hike to nearby hills—a gesture believed to represent personal growth and strength for the year ahead. Think of it as a spiritual trek with a side of fresh mountain air.

Pana Sankranti – Odisha

Pana Sankranti, also called Maha Vishuba Sankranti, kicks off the Odia New Year. It aligns with the Saka calendar, and as Odisha heats up in April, this festival brings a much-needed sense of cooling and calm.

The day’s highlight is the sweet drink Bela Pana, made with bael fruit, chhena, coconut, jaggery, pepper, and ginger. It’s an offering to Lord Shiva, Goddess Shakti, and Hanuman, meant to cool both the body and soul. A festival where hydration meets devotion? Very Odisha.

Ashadi Beej – Kutch, Gujarat

In the dry lands of Kutch, Ashadi Beej arrives as a whisper of hope. Celebrated in June or July, it marks the arrival of the monsoon—a sign of life, nourishment, and fresh farming cycles.

Kutchi communities greet the season with quiet anticipation. There’s no massive ritual, just a gentle reminder of nature’s rhythms and the way the land teaches us to begin again.

Nutan Varsh – Gujarati

While the rest of India may be winding down from Diwali, Gujaratis are just getting started with their New Year, known as Hindu Nutan Varsh or Bestu Varas. Celebrated the day after Diwali (on the first day of the Hindu Vikram Samvat calendar which began in 57 BCE, Kartik Shukla Pratipada), Nutan Varsh is all about fresh starts, family bonds, and a whole lot of sweet beginnings.

Sikkimese New Year

Sikkim, nestled in the Eastern Himalayas, is home to a rich mosaic of ethnic communities—each with its own way of marking the New Year.

- The Newar community observes Mha Puja, typically celebrated in October or November, as a ritual of self-purification and renewal.

- The Sherpas welcome their new year with Gyalpo Lhosar, falling between February and March, filled with prayer ceremonies and cultural performances.

- The Gurung community celebrates Tamu Lhosar in December, often marked by vibrant dances and communal feasts.

- For the Tamang people, Sonam Lhosar arrives in January or February and is a time for honoring ancestors and deities with songs and rituals.

- Lastly, Namsoong—also called Losoon—is observed by the Bhutia and Lepcha communities and marks the beginning of their traditional calendar year with deep-rooted spiritual and seasonal practices. Each of these festivals reflects not just a calendar shift, but a cultural heartbeat unique to Sikkim’s beautifully diverse heritage.

Losar – Arunachal Pradesh & Ladakh

Losar is the Tibetan New Year, observed in Ladakh and by the Monpa tribe in Arunachal Pradesh. Based on the Tibetan lunar calendar, which started in 1027 CE, this festival usually falls in February or March.

The celebrations go deep—literally and metaphorically. There are special offerings to deities, sacred chants, fire rituals, and traditional foods like Khapse (fried sweets). It’s a reset button for both space and spirit, observed in the coldest but most peaceful corners of India.

Sangken – Arunachal Pradesh

Sangken is the water festival of the Theravāda Buddhist tribes like the Khamti and Singpho. It’s celebrated mid-April and mirrors water festivals across Southeast Asia, like Songkran in Thailand.

Water, in Sangken, isn’t just playful—it’s symbolic. It washes away bad karma and past negativity, leaving space for renewal. People clean Buddha idols, pour water on each other, and come together in joy. It’s a soft, splashy start to the Buddhist New Year that dates back to 543 BCE, the year of Buddha’s Mahaparinirvana.

Nowruz – Persian New Year in India

After Persia was conquered, many Zoroastrians fled to India and became known as Parsis. But even as the world around them changed, they clung to the Shahenshahi calendar (dating back to 632 CE) and the traditions of Nowruz—the Persian New Year.

In India, Nowruz is observed with a table full of symbolic objects (called Haft-Seen), fire rituals, prayers, and community feasting. Though celebrated on slightly different dates from Iran, the energy is the same: gratitude, rebirth, and a toast to light.

So Many New Beginnings

Here’s the truth: India doesn’t celebrate the New Year once. It does it more than a dozens of times, in dozens of ways, across every landscape and language.

Each celebration—whether it’s Ugadi festival in Andhra Pradesh, Puthandu in Tamil Nadu, or Bohag Bihu in Assam—comes with its own story, flavor, and soul. And together, Indian New Year show us just how layered, diverse, and beautifully complex the idea of a “new beginning” can be.

So whether you celebrate one or many of these, may each one bring you closer to joy, peace, and your truest self. New Year in India isn’t about the clock—it’s about the moment you choose to start fresh.

![]()